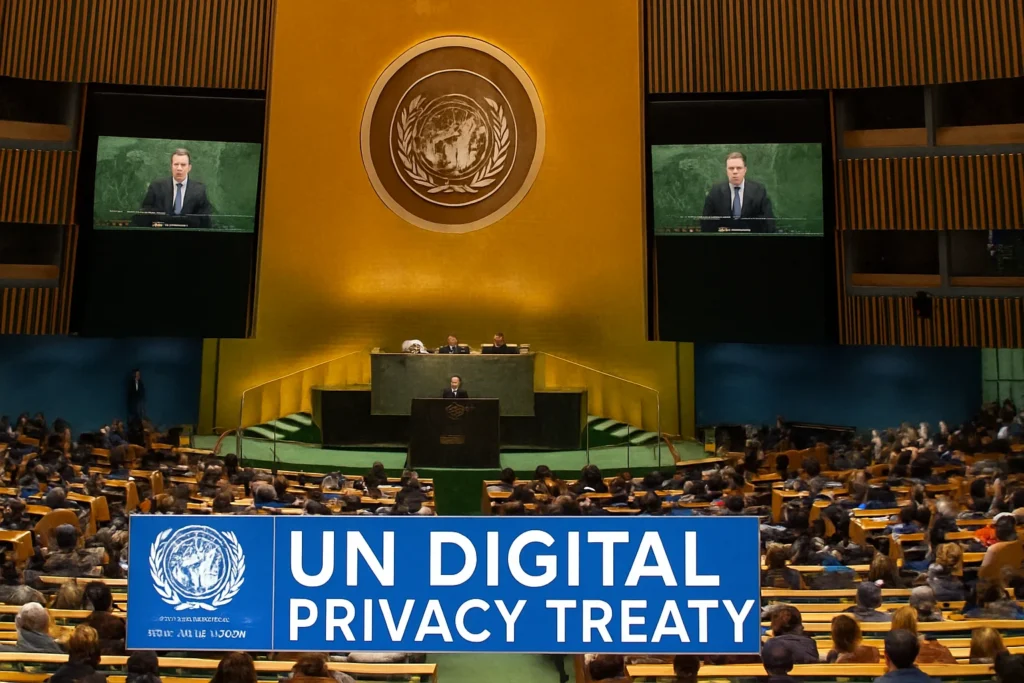

Introduction: The Digital Privacy Crisis That Forced the World to Act

In our modern, hyper-connected world, every online action—from a casual search for a recipe to a life-changing financial transaction—generates a digital footprint. This trail of personal data, a mosaic of our habits, beliefs, and identities, has become one of the most valuable commodities on the planet. For decades, this information was collected, analyzed, and traded by powerful tech giants and governments with minimal oversight. Operating in a vast regulatory gray area, these entities constructed what privacy advocates chillingly termed a “global surveillance economy,” where the individual’s right to control their own information was systematically eroded. Data brokers amassed dossiers on billions of people, selling insights to marketers and political campaigns, while sophisticated algorithms made crucial decisions about our lives—from credit scores to job opportunities—in opaque ways.

The inevitable breaking point arrived not with a single event, but with a cascade of high-profile data breaches that exposed the profound fragility of our digital infrastructure. News headlines chronicled the loss of sensitive medical records held for ransom, the theft of financial information sold on dark web marketplaces, and the unauthorized use of social media data to influence elections. The scale of these breaches, affecting billions of people across every continent, made the human cost of unregulated data practices impossible to ignore. It became clear that the internet’s decentralized nature had left individuals vulnerable to exploitation on a global scale. It was against this backdrop of widespread digital vulnerability and public outcry that the United Nations embarked on an ambitious journey to create the first comprehensive global digital privacy framework—a landmark treaty that would not just regulate technology, but fundamentally redefine the relationship between technology, governance, and fundamental human rights. This was a treaty born not out of foresight, but from the urgent necessity of a world where digital exploitation had spiraled out of control.

The Long Road to Digital Rights: Historical Context of Privacy Frameworks

The Foundational Principles of Privacy

The concept of privacy as a fundamental human right is not a modern invention but a principle with deep historical roots. Its formal recognition emerged from the ashes of World War II. In 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights boldly stated in Article 12: “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honor and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.” This was a remarkable act of foresight, establishing a philosophical cornerstone decades before the first personal computers or the internet’s birth. This principle was further reinforced in 1966 by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which in Article 17, reiterated this right. These foundational frameworks, while not tailored to the complexities of digital data, provided the moral and legal bedrock upon which all future digital rights discussions would be built.

The first specialized international instrument to address the unique challenges of digital data processing was the Council of Europe’s “Convention for Protection of Individuals with Regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data,” known as Convention 108, which was adopted in 1981. Heralded as a foundational blueprint, this treaty established core principles that would go on to influence privacy legislation across the globe. It introduced key concepts such as data quality, purpose limitation, and the right of access for individuals. Its principles were a direct response to the nascent threats posed by early computing systems. Convention 108 became the intellectual ancestor of more robust regional frameworks, most notably the European Union’s landmark General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which became a global standard-setter when it came into force in 2018.

The Digital Revolution Outpaces Regulation

As technology advanced at an exponential pace throughout the 1990s and 2000s, regulatory efforts struggled to keep up. The internet, designed as a borderless network, erased geographical boundaries for data flows, while innovations like cloud computing and social media created unprecedented challenges for privacy protection. The rise of social networks in the late 2000s, in particular, fundamentally changed the game. Suddenly, billions of people were voluntarily sharing intimate details of their lives, creating vast troves of personal information for tech companies to monetize.

By the early 2010s, it became clear that a patchwork of national laws and regional frameworks was woefully insufficient to address a problem that was fundamentally global. A data breach in one country could expose citizens in dozens of others. Governments in some nations were using these borderless data flows to conduct mass surveillance, further complicating the legal landscape. The United Nations began seriously addressing digital privacy concerns in 2013, with the General Assembly and Human Rights Council adopting numerous resolutions on “the right to privacy in the digital age.” These resolutions were a critical first step, as they affirmed that the same human rights people have offline—the right to privacy, freedom of expression, and assembly—must be protected online. This seemingly obvious principle had, in practice, been routinely ignored by both corporate and governmental actors who saw the digital space as a new frontier free from the constraints of traditional human rights law.

The 2013 revelations about mass surveillance programs marked a watershed moment that fundamentally altered the global conversation on digital privacy. For the first time, the general public became aware of how extensively their digital activities were being monitored, often without clear legal authorization or oversight. This awareness sparked global outrage and created the political momentum necessary for a comprehensive international response. Between 2014 and 2018, the UN conducted a series of expert consultations and commissioned reports on digital privacy that revealed both the urgent need for international standards and the significant challenges in achieving global consensus. Nations differed dramatically in their approaches to privacy, with some viewing it primarily as a consumer protection issue and others as a fundamental human right.

The process gained significant momentum with the implementation of the EU’s GDPR in 2018, which demonstrated that comprehensive privacy regulation was feasible and could even benefit the digital economy by increasing user trust. The GDPR became a de facto global standard, with many international companies extending its protections to users worldwide rather than maintaining separate systems. Meanwhile, developing countries began recognizing the importance of data protection not just for individual rights but for economic development and digital sovereignty. Many nations found themselves caught between competing regulatory frameworks and sought a neutral, internationally-developed standard that could accommodate diverse legal traditions and development levels.

Understanding the Treaty: Key Provisions and Revolutionary Protections

Core Principles and Rights

The UN Digital Privacy Treaty is built on a comprehensive framework of principles designed to create a global standard for data protection, shifting the burden of responsibility from the individual to the organizations that collect their data. It is a fundamental reframing of data governance, moving away from a model of permissive use to one of controlled access and accountability.

- Lawfulness, Fairness, and Transparency: This is the bedrock of the treaty. It mandates that all data collection must have a clear legal basis, such as informed consent, and must be conducted in a fair and transparent manner. This means organizations can no longer hide their data practices in long, unreadable privacy policies. They must be upfront about what they collect and why, using language that ordinary people can understand rather than legal jargon designed to obscure practices.

- Purpose Limitation: This principle is a direct attack on the “hoard everything” business model that has dominated the digital economy. It dictates that personal data can only be collected for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes. For example, a healthcare app that collects data for medical diagnosis cannot then sell that same data to a life insurance company for profit without obtaining fresh consent for this completely different purpose.

- Data Minimization: This principle pushes back against the trend of companies collecting vast quantities of data just “in case” it might be useful later. It mandates that only the data that is absolutely necessary for the stated purpose may be collected. This encourages a “less is more” approach to data collection, reducing both the risk of a massive breach and the temptation for companies to find new, potentially unethical uses for data they already possess.

- Accuracy: Personal data must be kept accurate and up-to-date. The treaty empowers individuals to challenge and correct incorrect information, a crucial right in a world where automated systems make decisions based on our digital profiles. An inaccurate data point could mean the difference between getting a loan or being denied, being shown relevant job opportunities or missing them completely.

- Storage Limitation: Data should not be kept in an identifiable form for longer than is necessary to fulfill the purpose for which it was collected. This prevents organizations from holding onto sensitive information indefinitely, thereby limiting the potential damage of a future breach. It forces companies to regularly review their data holdings and delete what they no longer need.

- Integrity and Confidentiality: The treaty requires organizations to implement appropriate security measures, both technical and organizational, to protect against unauthorized access, loss, or destruction of personal data. This places a clear, legally binding obligation on data holders to secure the information they control, with the required security level proportional to the risk presented by the data processing.

- Accountability: This is one of the most powerful principles. It states that data controllers are responsible for demonstrating compliance with the treaty. This shifts the burden of proof, requiring organizations to actively prove that they are protecting data, rather than requiring individuals to prove a violation. It transforms privacy from a defensive right to an affirmative obligation.

The Rights Granted to Individuals

The treaty dramatically shifts power from data holders to individuals through a suite of enforceable rights, giving people unprecedented control over their digital lives. These rights are not merely suggestions but legally binding obligations for all signatory nations.

- Right to Know: Individuals have the right to know what personal data is being collected about them, the purpose for its collection, and how it will be used. This right empowers users to make informed decisions about who they trust with their information and for what purposes.

- Right to Access: People can request and receive a complete copy of all personal data held by an organization in a portable, easy-to-read format. This right enables individuals to conduct their own audits and see exactly what a company knows about them, removing the mystery from corporate data collection practices.

- Right to Correction: Individuals may demand that inaccurate or incomplete data about them be corrected without undue delay. This is particularly vital in a world of algorithmic decision-making, where a single incorrect data point can have a devastating impact on a person’s access to credit, housing, or employment opportunities.

- Right to Deletion: Often called the “right to be forgotten,” this allows people to request that their data be erased under specific circumstances, such as when the data is no longer necessary for the purpose it was collected or when consent is withdrawn. This gives individuals a mechanism to clean up their digital footprint and start fresh when appropriate.

- Right to Object: Individuals can object to certain types of data processing, including processing for direct marketing or profiling. This gives users a powerful tool to opt out of targeted advertising and other forms of data-driven manipulation that have become ubiquitous in the digital economy.

- Right to Restrict Processing: People may request a temporary halt to data processing while challenges to the data’s accuracy or legality are being resolved. This acts as a protective shield, preventing a company from continuing to process data that is in dispute until the matter is settled.

- Right to Data Portability: Individuals can receive their personal data in a structured, commonly used, and machine-readable format, and have the right to transmit that data to another controller without hindrance. This promotes competition by making it easier for consumers to switch services without losing their historical data.

- Right to Human Review of Automated Decisions: Individuals have the right not to be subject to decisions based solely on automated processing, including profiling, that produce legal effects or similarly significant effects. This represents a crucial safeguard against algorithmic discrimination and ensures that important decisions about people’s lives retain a human element of judgment.

These rights represent a fundamental rebalancing of the digital ecosystem, placing individual autonomy and choice at the absolute center of data governance. The treaty is a powerful affirmation that data is a part of our identity and that we have a right to control it.

Special Protections for Vulnerable Groups

Recognizing that privacy violations disproportionately affect certain populations, the treaty includes enhanced protections for vulnerable groups:

- Children’s Data: Special protections apply to children’s personal data, recognizing that children may be less aware of the risks and consequences of data processing. The treaty requires parental consent for processing children’s data in many circumstances and prohibits certain types of processing that might exploit children’s vulnerability, such as targeted advertising based on their online behavior.

- Journalists and Activists: Additional safeguards protect the data of journalists, human rights defenders, and political activists, whose work often makes them targets of surveillance and data exploitation. These protections are crucial for preserving freedom of the press and protecting democratic processes around the world.

- Marginalized Communities: The treaty acknowledges that data processing can perpetuate discrimination and requires special attention to protecting marginalized communities from having their data used in ways that might reinforce existing inequalities. This includes protections against algorithmic bias that might disproportionately affect certain racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic groups.

The Diplomatic Journey: How the World Community Reached Consensus

Negotiation Challenges and Breakthroughs

The path to agreement was a five-year-long diplomatic marathon, marked by intense debates and complex negotiations. The process involved a diverse group of stakeholders, including nation-states, international organizations, civil society groups, and industry representatives. The negotiations were often fraught with tension, as they pitted the competing interests of privacy-focused nations against security-minded states and the business models of the world’s largest tech companies.

Privacy-focused nations, often led by European countries with a strong tradition of data protection, pushed for a treaty with strong, enforceable protections, advocating for a human rights-based approach. On the other side were security-minded states, which expressed concern that strict privacy protections might hamper their ability to combat cybercrime, terrorism, and other national security threats. This ideological divide was a constant challenge throughout the negotiation process.

The initial drafting process involved hundreds of diplomats, legal experts, technologists, and civil society representatives. Early versions of the treaty faced significant opposition from several directions: some countries worried about the impact on their surveillance capabilities, others expressed concern about the compliance burden on businesses, and still others questioned whether a one-size-fits-all approach could work for nations at different levels of economic development.

The breakthrough came with the inclusion of two key compromises. First, the treaty incorporated a flexible implementation framework. This meant that while all signatory nations were obligated to meet the treaty’s core principles, they could do so through their own domestic legal systems, rather than adopting a single, rigid legal code. This flexibility was crucial in securing support from a diverse coalition of nations with different legal traditions. Second, the negotiators established special provisions for national security, which required any data collection for security purposes to be lawful, necessary, and proportional—a crucial safeguard that provided a check on potential government overreach while still allowing for legitimate security activities.

Perhaps the most challenging negotiations centered on cross-border data transfers. Some nations advocated for strict limitations on data flows to countries with weaker privacy protections, while others argued for more open data flows to support digital trade. The final compromise created a tiered system that allows data transfers under certain conditions, including adequacy decisions, binding corporate rules, and specific contractual clauses.

Another significant hurdle was establishing the treaty’s relationship with existing regional frameworks like the GDPR. Some European nations initially worried that the treaty might undermine their already-robust protections, while other countries feared they would be forced to adopt European standards wholesale. The solution was to design the treaty as a floor rather than a ceiling—establishing minimum standards that all nations must meet while allowing countries or regions to maintain or enact stronger protections.

The Final Vote and Absentions

When the final vote arrived at the UN General Assembly, the outcome reflected both a remarkable global consensus and persistent divisions. The vote was a powerful demonstration of the international community’s recognition that digital privacy had become a truly global priority. Over 120 member nations voted in favor of the treaty, a broad coalition that included countries from every region and development level. This was a testament to the fact that the digital privacy crisis affected everyone, not just the wealthy or technologically advanced nations.

The voting patterns revealed interesting geopolitical alignments. European nations voted overwhelmingly in favor, reflecting their longstanding commitment to data protection. Many African and Latin American countries also supported the treaty, seeing it as an opportunity to establish clear rules for multinational tech companies operating in their territories. Several Asian nations with strong digital economies supported the agreement, recognizing that privacy protections could enhance user trust and stimulate digital innovation.

A handful of countries, however, abstained from the vote, citing concerns about national sovereignty and potential constraints on their existing security operations. These nations expressed worry that the treaty’s requirements might complicate their existing surveillance programs and cybercrime prevention efforts. Some countries also raised concerns about the implementation costs, particularly for developing nations with limited administrative capacity.

Despite these abstentions, the treaty moved forward with overwhelming support, its passage setting the stage for a new era in global digital governance. The vote was a clear signal that the world was no longer willing to allow the free flow of data without a clear set of human-centric rules. The widespread endorsement sent a powerful message that the international community was ready to establish clear rules for the digital age.

Global Implications: How the Treaty Will Transform Business and Government Practices

Impact on International Business Operations

The UN Digital Privacy Treaty creates a uniform baseline for data protection that will have profound implications for businesses operating across borders. For multinational corporations, the treaty will simplify compliance while simultaneously raising the global standard for data protection. Businesses that once had to navigate a complex and fragmented patchwork of national laws now face a consistent set of expectations across all signatory nations. This will reduce administrative complexity and foster a more stable global digital marketplace.

For U.S. and foreign-owned companies operating internationally, the treaty necessitates a comprehensive and immediate review of all data handling practices. Organizations must now implement robust data governance frameworks, including detailed data mapping to understand where personal information is stored and processed, and classification systems to categorize data by sensitivity. The treaty also mandates privacy-by-design approaches, which means that data protection must be integrated into the entire lifecycle of a product or service, from the initial design phase. This marks a significant shift from a reactive, security-focused model to a proactive, privacy-centric one.

The treaty also imposes specific and powerful restrictions on cross-border data transfers, requiring that personal data can only be transferred to countries with adequate privacy protections. This provision has the potential to fundamentally reshape global data flows, encouraging a more responsible and secure approach to international data management. Companies will need to establish rigorous mechanisms for ensuring that international data transfers comply with the treaty’s standards, potentially including new contractual arrangements, binding corporate rules, or obtaining explicit consent from individuals for specific transfers.

The treaty’s impact extends beyond compliance requirements to fundamentally change business models built on extensive data collection. Companies that previously relied on covert data gathering or secondary uses of personal information must now redesign their practices around transparency and user control. This shift may initially challenge some digital business models, but many experts believe it will ultimately foster more sustainable relationships between companies and their users based on trust rather than exploitation.

Table: Key Business Requirements Under the UN Digital Privacy Treaty

| Requirement | Description | Timeline for Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Protection Impact Assessments | Mandatory assessments for high-risk processing activities | Within 2 years of ratification |

| Privacy by Design | Integration of data protection into product development | Within 3 years of ratification |

| Cross-Border Transfer Safeguards | Adequate protections for international data transfers | Immediate upon ratification |

| Data Breach Notification | Prompt notification of breaches to authorities and individuals | Immediate upon ratification |

| Annual Compliance Audits | Independent verification of privacy compliance | Within 3 years of ratification |

| Data Protection Officers | Designation of responsible personnel for compliance | Within 1 year of ratification |

| Records of Processing Activities | Comprehensive documentation of data processing | Within 2 years of ratification |

| Data Protection Training | Regular training for employees handling personal data | Within 1 year of ratification |

New Government Obligations and Enforcement Mechanisms

The treaty establishes mandatory requirements for all signatory states, ushering in a new era of accountability for governments. Nations must now create independent data protection authorities with sufficient resources and legal powers to investigate violations and impose meaningful penalties. These authorities must be empowered to conduct audits, issue warnings, and levy significant financial penalties for non-compliance. The treaty provides a framework for these penalties, ensuring they are proportional and dissuasive, with fines potentially reaching up to 4% of global annual turnover for companies—mirroring the GDPR’s approach to ensure multinational corporations take their obligations seriously.

Perhaps most importantly, the treaty creates an international oversight mechanism that will regularly review implementation across countries and facilitate cooperation between national authorities. This mechanism represents an unprecedented level of global coordination on digital privacy issues. It will allow authorities to share best practices, exchange information about privacy violations, and even collaborate on investigations into multinational corporations. This creates a form of mutual enforcement, where a violation in one country can trigger action in others, thereby addressing the borderless nature of digital data and holding both corporations and governments accountable to their commitments.

The treaty also requires governments to review their existing laws and regulations for compatibility with the new standards. This may necessitate changes to surveillance laws, national security protocols, and public sector data handling practices. Many countries will need to establish new legal frameworks for government data processing, bringing public sector activities under similar privacy constraints as the private sector. This represents a significant shift for many governments that have traditionally exempted themselves from the privacy rules they impose on corporations.

For developing countries, the treaty includes provisions for technical assistance and capacity building. Wealthier nations are encouraged to support implementation efforts in countries with limited resources, recognizing that effective privacy protection requires investment in institutional infrastructure, technical expertise, and public education. This assistance is crucial for preventing the emergence of a “privacy divide” where only wealthy nations can afford to protect their citizens’ digital rights.

Enforcement Challenges: From Paper to Practice in a Fragmented World

The Implementation Gap

While the treaty sets forth ambitious standards, its ultimate effectiveness hinges on its domestic implementation. The history of international law is littered with examples of well-intentioned agreements that were undermined by weak enforcement at the national level. The UN Digital Privacy Treaty attempts to address this through detailed reporting requirements and technical assistance provisions for developing countries, but significant challenges remain. Many nations lack the legal and technical expertise to overhaul their domestic laws and create a new data protection authority from scratch. The financial cost of building a robust regulatory body and training a new generation of data privacy experts is a significant hurdle, particularly for countries with limited resources.

The implementation timeline, which allows countries three to five years to bring their domestic laws into compliance with treaty obligations, is a pragmatic recognition that such legal and administrative changes happen gradually. This transition period is crucial for nations with limited institutional capacity or those needing comprehensive legal reforms. However, it also creates a temporary patchwork of standards and could lead to enforcement disparities in the early years of the treaty’s life.

The success of implementation will vary significantly across countries. Nations with existing data protection frameworks, particularly those that have already adopted GDPR-like regulations, will face relatively straightforward adaptation processes. Countries without comprehensive privacy laws will need to build their regulatory infrastructure essentially from scratch—a process that requires not just legislation but also developing institutional expertise and cultural awareness about the importance of data protection.

Another implementation challenge involves the treaty’s flexibility provisions. While necessary to achieve broad adoption, these flexible elements create the risk of inconsistent interpretation and application across different jurisdictions. Some privacy advocates worry that countries might use the flexibility to create loopholes or maintain weak protections in practice, potentially undermining the treaty’s overall effectiveness. There is also concern that some nations might adopt the treaty in name only, creating the appearance of compliance without the substance.

Monitoring and Compliance Mechanisms

The treaty establishes a Committee of Experts composed of independent specialists who will review periodic implementation reports from each country. This committee can make recommendations for improving compliance and highlight areas of concern, thereby using the power of public scrutiny to encourage nations to fulfill their obligations. While this committee lacks strong enforcement powers, its ability to “name and shame” non-compliant nations can be a powerful tool for driving change, particularly in democracies where governments are sensitive to international reputation.

Perhaps the most powerful enforcement mechanism, however, is likely to be the cross-border recognition of privacy violations. The treaty facilitates information sharing and collaboration between national authorities, allowing for a form of mutual enforcement. If a company violates a citizen’s rights in one country, the data protection authority there can alert its counterparts in other signatory nations, potentially leading to coordinated investigations and fines. This creates a powerful deterrent, as a violation in a single country could now have global ramifications for a business.

The treaty also includes provisions for international cooperation on enforcement, including mutual legal assistance and joint investigation frameworks. These mechanisms are particularly important for addressing violations by multinational companies that operate across numerous jurisdictions. They allow authorities to pool resources and expertise when tackling complex cross-border cases, making it more difficult for companies to engage in “jurisdiction shopping” by basing their operations in countries with weak enforcement.

Despite these mechanisms, the treaty’s effectiveness will ultimately depend on political will at the national level. Countries that are reluctant to enforce privacy protections may do the minimum necessary to avoid international criticism, creating enforcement gaps that undermine the overall framework. Maintaining consistent pressure for implementation will require ongoing engagement from civil society, industry stakeholders, and the international community.

Technological Innovation and Privacy: Finding the Balance

Emerging Technologies and Privacy Challenges

The treaty arrives at a critical moment of technological convergence, with artificial intelligence, biometric surveillance, and predictive analytics creating unprecedented privacy challenges. These technologies can process enormous quantities of personal information in ways that are increasingly invisible to individuals. AI-powered systems can use facial recognition to identify people in public spaces, analyze voice patterns to infer emotional states, and use our past behavior to predict future actions—all without our conscious knowledge or consent. This creates what privacy advocates call a “black box society,” where important decisions about our lives are made without transparency or accountability.

Artificial intelligence systems, particularly machine learning algorithms, often rely on vast datasets for training and operation. These systems can infer sensitive information from seemingly innocuous data, creating privacy risks that traditional consent models may not adequately address. For example, an algorithm might deduce a person’s sexual orientation, political views, or health conditions from their online behavior patterns, even if that information was never explicitly shared. The treaty attempts to address these challenges by establishing principles for algorithmic transparency and requiring human review of significant automated decisions.

Biometric technologies, including facial recognition, gait analysis, and voice identification, present particularly acute privacy concerns. These technologies can enable identification and tracking without individuals’ knowledge or consent, potentially creating perpetual surveillance environments. The treaty imposes strict limitations on biometric data processing, requiring heightened safeguards and in many cases explicit consent. This is particularly important as biometric data is inherently unique and immutable—unlike a password, you cannot change your face or fingerprints if this data is compromised.

The Internet of Things (IoT) ecosystem creates another frontier for privacy challenges. With billions of connected devices collecting information about our homes, bodies, and environments, the scale of data collection has expanded dramatically. Smart devices in our homes can track our movements, eating habits, and entertainment preferences; wearable devices can monitor our health metrics and sleep patterns; smart city infrastructure can track our movements through urban spaces. The treaty’s data minimization and purpose limitation principles are particularly relevant to IoT, encouraging manufacturers to collect only necessary data and to be transparent about their practices.

The treaty addresses these challenges through a set of technology-neutral principles that apply regardless of the specific technical implementation. This flexible approach ensures that the framework remains relevant as technology continues to evolve. While the treaty doesn’t provide specific rules for every new technology, its foundational principles of purpose limitation, data minimization, and accountability provide a robust framework for regulating the privacy implications of new technologies. This may, however, necessitate supplementary guidelines for specific emerging technologies in the future.

The Innovation Argument: Critique and Response

Some critics have argued that strict privacy protections could stifle innovation by creating significant compliance burdens and limiting data access. They argue that data is the “new oil” and that limiting its flow will hamper economic growth and technological progress. This perspective suggests that privacy regulations create barriers to the free flow of information that drives innovation in areas like artificial intelligence, medical research, and urban planning.

The treaty attempts to balance these concerns through provisions that encourage privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) and anonymous data use for research purposes. These technologies allow for data analysis and innovation while protecting individual identities. Techniques such as differential privacy, federated learning, and homomorphic encryption enable valuable insights to be extracted from data without exposing personal information. By promoting these technologies, the treaty aims to foster innovation that respects privacy rather than innovation that exploits personal data.

Rather than inhibiting innovation, the treaty may actually stimulate it by creating a level playing field with clear rules. Many technology companies have expressed support for uniform global standards, which could reduce the compliance complexity of navigating a patchwork of different laws and increase public trust in digital services. When consumers trust that their data will be handled responsibly, they may be more willing to engage with new technologies and share information for beneficial purposes.

The treaty also recognizes the importance of scientific research and statistical analysis, creating specific exceptions for these activities when appropriate safeguards are in place. This balanced approach acknowledges that some socially beneficial data uses may require flexibility while maintaining core protections. Research institutions can apply for exemptions to use personal data without consent when the research serves an important public interest and cannot practically be conducted with anonymized data.

Privacy-enhancing technologies themselves represent a growing field of innovation. As the treaty creates demand for better privacy protections, it may accelerate development and adoption of these technologies. Companies that develop effective PETs may find new market opportunities, while organizations that learn to innovate within privacy constraints may gain competitive advantages in increasingly privacy-conscious markets.

Voices of Support and Criticism: Various Perspectives on the Treaty

Human Rights Organizations React

Human rights groups have overwhelmingly praised the treaty as a historic advancement for digital rights. Organizations that have long advocated for privacy protections see the agreement as a powerful validation of their argument that privacy is a fundamental human right that must be protected in the digital age. They have particularly highlighted the treaty’s emphasis on individual rights and its recognition that privacy violations disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, including journalists, activists, and minority groups. For these communities, strong privacy protections can be a matter of physical safety, not just a matter of personal preference.

Human Rights Watch described the treaty as “a watershed moment for digital rights that establishes crucial protections for everyone in an increasingly monitored world.” Amnesty International called it “the most significant advance in human rights protection since the adoption of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989.” These organizations have emphasized that the treaty represents a crucial check on both corporate and government power, helping to prevent the emergence of digital authoritarianism where citizens are constantly monitored and their data exploited without consent.

Privacy advocacy organizations have emphasized the importance of robust implementation and warned against attempts to weaken the treaty’s provisions through domestic legislation. They have pledged to monitor implementation closely and hold governments accountable for their commitments. These groups have particularly emphasized the need to protect the treaty’s protections for vulnerable groups, including journalists, activists, and marginalized communities, who often bear the brunt of privacy violations.

Industry and Government Concerns

While generally supportive of a global standard, some industry representatives have expressed concerns about the treaty’s implementation costs and potential conflicts with existing frameworks. The business community has emphasized the need for flexibility and proportionality in enforcement, particularly for small and medium enterprises with limited resources. They have argued that a one-size-fits-all approach to compliance could place an undue burden on small businesses, stifling their ability to compete with larger corporations.

Technology industry associations have generally welcomed the treaty’s harmonization of global standards while urging reasonable implementation timelines and clear guidance for businesses. Some industry groups have called for additional exceptions for data uses that present low privacy risks, arguing that overly broad restrictions could inhibit beneficial innovations. There are also concerns about the potential fragmentation of global data flows if the treaty’s restrictions on international data transfers are implemented too strictly.

Some governments have also raised sovereignty concerns, arguing that the treaty could interfere with legitimate law enforcement and national security activities. These concerns were partially addressed through the exceptions for security purposes, but disagreements persist about the appropriate balance between privacy and security. The ongoing debate highlights the complex tradeoffs inherent in modern governance and the difficulty of creating a single framework that satisfies every nation’s unique security priorities.

Several countries have expressed concern about the treaty’s potential impact on their digital economic development. Developing nations in particular worry about the costs of establishing and maintaining robust data protection authorities and whether the treaty might disadvantage their emerging digital industries. There are concerns that strict privacy rules could make it more difficult for startups in developing countries to compete with established tech giants that have more resources to achieve compliance.

The Road Ahead: Implementation Timeline and Next Steps

Ratification and Early Implementation

The treaty will open for formal signature at a ceremony in Hanoi, Vietnam, in 2025, marking the beginning of the ratification process. The treaty will enter into force 90 days after the 40th country deposits its ratification instrument—a crucial threshold that supporters hope to reach within two to three years. This ratification process will be a test of political will, as each nation must choose to incorporate the treaty’s principles into its domestic law. The process will involve complex legislative changes in many countries, as they align their existing laws with the treaty’s requirements.

Early implementation efforts are already underway through capacity-building initiatives led by the UN and its partner organizations. These programs help countries assess their current privacy frameworks, identify gaps, and develop action plans for compliance. Developed countries are expected to provide technical and financial assistance to developing nations to ensure equitable implementation and prevent the creation of a global privacy divide where only a few nations have robust protections. This assistance may include funding for regulatory bodies, training programs for data protection professionals, and support for public education campaigns about digital rights.

The first years after the treaty enters into force will focus on establishing the international oversight mechanisms and developing detailed guidance for implementing specific provisions. This guidance will help ensure consistent interpretation across different jurisdictions and prevent the fragmentation that the treaty aims to overcome. The Committee of Experts will play a crucial role in this process, providing interpretations of ambiguous provisions and establishing best practices for implementation.

Many countries have already begun aligning their domestic laws with the treaty’s requirements in anticipation of ratification. This pre-implementation work suggests strong commitment to making the treaty effective and may accelerate the global harmonization of privacy standards. Some nations are using the treaty as an opportunity to comprehensively update their privacy laws, creating modern frameworks that address current technological challenges rather than simply patching outdated legislation.

The Future of Digital Privacy Governance

The UN Digital Privacy Treaty represents a beginning rather than an endpoint in global privacy governance. As technology continues to evolve at a relentless pace, the framework will need to adapt and expand to address new challenges. The agreement establishes procedures for regular review and amendment, recognizing that digital privacy is a dynamic issue requiring ongoing attention. These review processes will allow the treaty to incorporate lessons from implementation and address emerging technologies that may not have been contemplated during the original negotiations.

Looking further ahead, the treaty may inspire similar global frameworks for other digital rights issues, potentially creating a comprehensive international governance structure for the digital sphere. This could include areas like artificial intelligence ethics, platform accountability, and digital competition policy, setting a precedent for global cooperation on complex technological challenges. The treaty’s success or failure will likely influence whether nations pursue additional multilateral agreements to govern the digital economy or retreat toward fragmented national approaches.

The treaty also establishes a precedent for multistakeholder involvement in digital governance, incorporating input from civil society, technical experts, and industry representatives alongside government perspectives. This inclusive approach may become a model for future international agreements on digital issues, recognizing that effective governance requires expertise and perspectives from beyond the diplomatic community. This approach helps ensure that regulations are technically feasible, economically sustainable, and protective of fundamental rights.

As implementation progresses, the treaty’s success will be measured not just by the number of countries that ratify it, but by tangible improvements in how personal data is handled worldwide. Ultimately, the treaty’s legacy will be determined by whether it delivers on its promise to protect individual privacy in our increasingly digital world. Success would mean that people around the world can benefit from digital technologies without sacrificing their fundamental right to privacy, creating a digital environment that serves human dignity rather than undermining it.

Conclusion: A New Era for Digital Rights and Global Cooperation

The adoption of the UN Digital Privacy Treaty marks a historic milestone in the decades-long struggle to bring human rights principles into the digital age. By establishing comprehensive global standards for data protection, the international community has affirmed that privacy is not a luxury or a technicality but a fundamental human right that must be protected regardless of technological context. The treaty is a powerful rejection of the notion that technology companies and governments should have unlimited access to personal information, instead asserting that individual control, transparency, and accountability must be at the center of our digital ecosystem.

The treaty’s adoption demonstrates that global cooperation on digital governance is possible despite different cultural traditions, legal systems, and economic interests. In a world often divided on technological issues, the overwhelming support for the treaty offers hope that the international community can come together to address the challenges of digitalization while upholding fundamental values. The collaborative process that produced the treaty, involving nations from all regions and development levels, suggests a growing recognition that digital rights are human rights and that their protection requires international cooperation.

While the challenges of implementation and enforcement are significant, the treaty provides a crucial foundation for building a digital future that respects human dignity and autonomy. Its true test will be whether it can translate its ambitious principles into meaningful, real-world protections for people in their daily lives. This will require sustained political will, adequate resources for implementation, and ongoing engagement from civil society to hold governments and corporations accountable to their commitments.

If successful, the treaty could serve as a model for how the international community can collectively address the challenges of technological change while upholding fundamental values. In a world increasingly shaped by digital interactions, this agreement offers a profound hope that our rights will not be left behind as we move into the future. It is a powerful statement that technology must serve humanity, not the other way around, and that even in our interconnected digital world, the right to privacy remains an essential component of human freedom and dignity.

The UN Digital Privacy Treaty represents more than just a set of rules—it embodies a vision of a digital future where technology enhances rather than diminishes human autonomy, where innovation serves rather than exploits individuals, and where global cooperation creates protections that no single nation could achieve alone. As this vision becomes reality through implementation, the treaty may come to be seen as a turning point in how humanity governs technology and protects fundamental rights in the digital age.

you’re actually a excellent webmaster. The website loading pace is amazing. It kind of feels that you’re doing any distinctive trick. In addition, The contents are masterwork. you have done a great task in this topic!

What’s Taking place i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have discovered It absolutely helpful and it has aided me out loads. I hope to contribute & help different customers like its aided me. Good job.

You are a very capable individual!

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was looking for!

I am always browsing online for posts that can facilitate me. Thank you!

It?¦s really a cool and helpful piece of info. I am glad that you just shared this useful info with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

I genuinely enjoy looking through on this web site, it has excellent posts.

I would like to thank you for the efforts you have put in writing this website. I’m hoping the same high-grade web site post from you in the upcoming also. Actually your creative writing abilities has encouraged me to get my own website now. Actually the blogging is spreading its wings rapidly. Your write up is a great example of it.

I was looking at some of your posts on this internet site and I believe this site is very instructive! Keep on posting.

Hi, Neat post. There is an issue with your site in web explorer, could check thisK IE still is the marketplace chief and a huge portion of other folks will omit your excellent writing because of this problem.