Prologue: The Breath of the Frozen Earth

There is a place on this planet where time moves differently. It is not measured in hours or days, but in millennia. The ground here is not dirt and rock as we know it—it is a library. A freezer. A vault. Buried beneath the moss and the stunted willow shrubs of Siberia, Alaska, and Northern Canada lies a secret so vast that scientists are only now beginning to understand its true weight.

If you could dig straight down through the permafrost, you would travel backwards through history. At three meters, you might find the bones of a steppe bison that grazed here when the pyramids were being built. At ten meters, you might find the tusk of a woolly mammoth, still ivory-white, that died when sea levels were a hundred meters lower than they are today. At thirty meters, you would find soil that froze solid two million years ago, before modern humans ever walked out of Africa. At fifty meters, the ice wedges grow thick as tree trunks, crystalline veins pulsing through the earth. At one hundred meters, the pressure alone has transformed loose silt into stone-hard permafrost that rings like ceramic when struck with a steel probe.

This frozen ground contains the remains of countless summers. Leaves that fell and never decayed. Grasses that died and never rotted. Animals that perished and never decomposed. Roots that reached downward and were stopped cold, frozen mid-growth. Normally, when plants and animals die, they release their carbon back into the air. Fungi consume them. Bacteria break them down. Worms pull them into the soil. But here, in the Arctic, the cold pressed pause. It reached down with icy fingers and said: not yet. Wait. Stay.

The carbon stayed. Two thousand billion tons of it. That is twice the amount of carbon currently floating around in the entire atmosphere of Earth. That is roughly equivalent to the combined carbon content of every tropical rainforest on the planet, multiplied by three. That is the weight of one hundred billion adult African elephants, frozen solid and buried beneath our northernmost lands.

For fifty thousand years, this system worked. The cold preserved the carbon, and the carbon stayed out of the air. Ice Age followed interglacial; sea levels rose and fell; glaciers advanced and retreated; mammoths evolved, thrived, and vanished. Through it all, the permafrost held. But the cold is leaving.

The Arctic is now warming four times faster than the rest of the planet. What took fifty thousand years to freeze is now thawing in decades. Not centuries. Decades. And as it thaws, the ancient carbon wakes up. Microscopic bacteria that have been dormant since before the invention of agriculture, since before the domestication of wolves, since before Homo sapiens reached the Americas—these bacteria stir to life. They find a feast of organic matter waiting for them, a buffet of frozen salad that has been marinating in permafrost brine for millennia. They eat. They multiply. They respire. And they breathe out carbon dioxide and methane.

This is not a slow process. It is happening right now. Scientists flying over Siberia in helicopters have spotted massive craters exploding out of the earth—pressure releases from methane gas that has been building beneath the thawing soil, accumulating until the ground literally bursts like an overinflated balloon. Rivers that have run clear for thousands of years are turning orange as iron-oxidizing bacteria, previously locked in frozen ground, leach into the waterways and stain them the color of rust. Houses built on pilings driven deep into the permafrost are tilting and collapsing as the ground that once held them solid turns to sludge. Airports are resurfacing runways every three years instead of every twenty. Pipelines are installing refrigeration units every few kilometers to keep the soil frozen beneath their supports.

We have a name for this. We call it the feedback loop. A warming world thaws the permafrost. Thawing permafrost releases greenhouse gases. Those gases warm the world more. More warming, more thaw. More thaw, more gas. More gas, more warming. It is the climate equivalent of pulling a thread on a sweater—keep pulling, and the whole thing unravels. Except the sweater is the stability of the planetary climate system, and the thread is being pulled by seven billion people burning fossil fuels.

But here is the strange part. The solution to this billion-ton problem does not require billion-dollar technology. It does not require rare earth minerals mined from conflict zones. It does not require space lasers or orbital sunshades. It does not require carbon capture machines that cost as much as a navy aircraft carrier and consume as much energy as a small city.

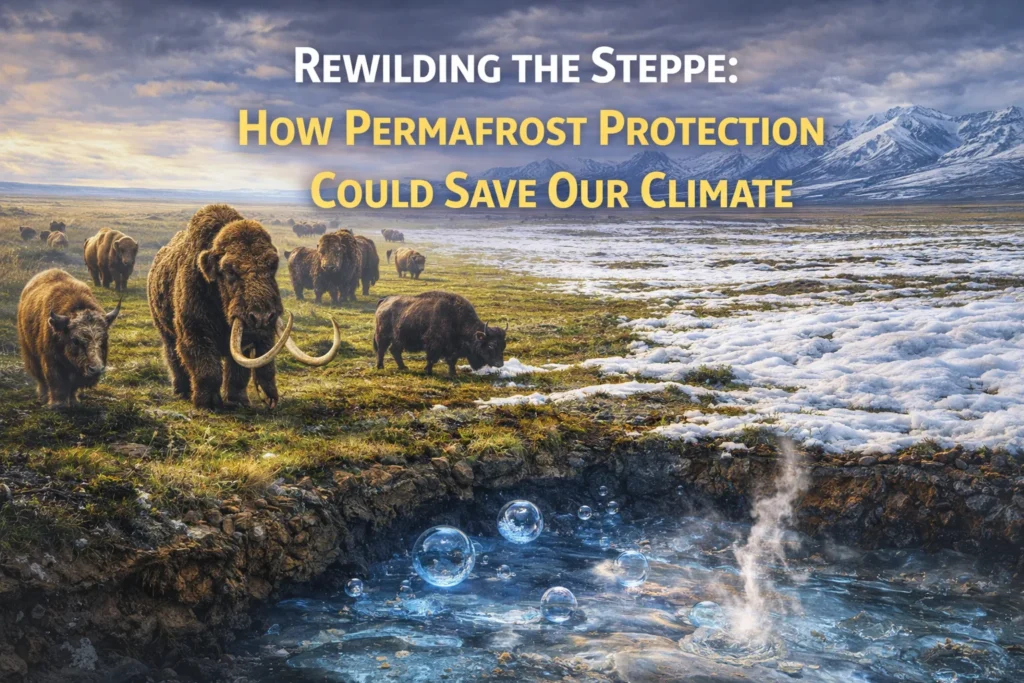

It requires horses.

It requires bison, reindeer, and musk oxen. It requires herds so vast that they darken the horizon and hooves so numerous that they churn the snow into a frozen crust. It requires bringing back an ecosystem that has been extinct for ten thousand years. It requires reintroducing animals that have not walked the Arctic tundra since the last remnants of the Ice Age withered away. It requires rewilding the steppe.

This is the story of how a handful of scientists, a father and son in the coldest part of Siberia, and a growing army of shaggy, cold-hardy herbivores are attempting to re-freeze the Arctic. It is a story of ancient grasslands, vanished mammoths, and the radical idea that sometimes the best way forward is to look backward. It is a story about the power of life to regulate the planet—not through technology, not through engineering, but through the simple, ancient act of grazing.

Part One: The Ground Beneath Our Feet

What Permafrost Actually Is

Let us clear up a common misunderstanding. Permafrost is not permanent. It never was. The word itself is a bit of geological marketing—a label that stuck because it sounded definitive. In truth, permafrost is simply ground that has remained at or below zero degrees Celsius for at least two consecutive years. Two years. That is the threshold. That is all it takes to earn the name.

In some places, permafrost has held steady for tens of thousands of years. In others, it is younger, having formed during the Little Ice Age a few centuries ago, when advancing glaciers and cooler summers allowed frozen ground to expand southward into regions that had been thawed for millennia. In still others, permafrost is actively forming today, in recently exposed riverbanks and freshly drained lake beds. It is dynamic. It is alive. It responds.

But regardless of its age, permafrost is not solid ice. It is soil—sand, silt, gravel, and organic matter—with ice crystals wedged between the particles. Think of it less like a glacier and more like a frozen sponge. Or better yet: think of it like a freezer-burned steak, dehydrated and tough on the outside but still moist within. The ice occupies the pore spaces, cementing everything together into a rigid matrix.

When permafrost thaws, the ice melts, but the water has nowhere to go because the ground beneath is still frozen. The water accumulates. The soil saturates. The rigid matrix collapses. What was solid becomes liquid. What was stable becomes mobile. The result is a soupy, saturated muck that cannot support weight. Trees that once stood upright begin to lean drunkenly—a phenomenon scientists have named, with characteristic understatement, “drunken forest.” Roads buckle and heave, their asphalt surfaces cracking into jigsaw puzzles. Pipelines twist and strain, their supports tilting at alarming angles. The land itself slumps and slides, creating a scarred, pockmarked terrain that looks less like Earth and more like the surface of a geologically active moon.

Entire islands are disappearing. Along the Arctic coast of Alaska and Canada, erosion rates have doubled and tripled over the past two decades. Coastal permafrost bluffs that once retreated a meter per year now lose ten meters annually. Communities that have stood for centuries are being relocated inland at enormous cost. Ancient cemeteries are collapsing into the sea, releasing remains that have been interred for generations. This is not hypothetical. This is not future tense. This is now.

But the physical collapse, dramatic as it is, is not the main concern. The main concern is what is inside that soil.

The Carbon Vault

When a leaf falls in a temperate forest, it decomposes within months. Worms consume it. Fungi infiltrate it. Bacteria break down its cellulose. Within a single growing season, the leaf is gone, its carbon released back into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, where it is promptly sucked up by the next generation of trees. It is a closed loop, a steady cycle, a perpetual motion machine powered by sunlight and soil moisture.

In the Arctic, that cycle broke down long ago. Leaves fell, grasses died, animals perished—but the cold prevented decomposition. Instead of rotting, the organic matter simply accumulated. Layer upon layer, millennium upon millennium. It piled up so deep that in some places the permafrost extends half a kilometer down. Five hundred meters of frozen history. Five hundred meters of undecayed life.

Geologists estimate that the northern permafrost region contains approximately 1,600 billion tons of carbon. To put that number in perspective, humans have released about 500 billion tons of carbon from fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution. The permafrost contains three times that amount. It is a carbon bomb with a very long fuse, and the fuse is burning shorter every year.

The problem is compounded by the fact that permafrost carbon is not just stored as carbon dioxide. Much of it is stored as methane. Methane is the nightmare cousin of carbon dioxide. It does not last as long in the atmosphere—about a decade versus centuries—but while it is there, it traps heat approximately 80 times more effectively. A pulse of methane from the Arctic could undo decades of emissions reductions in a single season. It could push us past tipping points from which there is no return.

And here is the truly unsettling part: we do not know exactly how much methane is down there. We have estimates, but estimates are not measurements. The permafrost is vast and remote; we have drilled only a tiny fraction of its extent. There could be methane hotspots we have not yet discovered, super-emitting seeps we have not yet located, geological reservoirs of ancient gas that have been trapped beneath ice for millions of years and are only now beginning to leak. We are flying blind over a frozen ocean of carbon.

The Thermokarst Terrain

Walk across undisturbed permafrost, and you might not realize anything is wrong. The ground feels solid beneath your boots. The moss is springy, a thick carpet of sphagnum that squeaks under pressure. The dwarf birches rustle in the wind, their leaves no larger than a child’s fingernail. Ptarmigan burst from the underbrush with a startling whir of wings. Arctic foxes leave delicate tracks in the snow. Everything seems normal. Everything seems timeless.

But look closer. Look for the cracks.

Thermokarst is the name geologists give to land that has collapsed due to thawing ice. It begins with an ice wedge—a vertical sheet of pure ice that has formed in a crack in the soil, sometimes over centuries. Water seeps into the crack in summer, freezes in winter, expands, and widens the crack. Repeat this process ten thousand times, and the ice wedge grows as wide as your arm, then your leg, then your torso. Some ice wedges in Siberia are three meters across and ten meters deep.

When the top of that wedge melts, water pools in the depression. That water is dark, much darker than snow or ice. It absorbs sunlight efficiently and transfers heat deeper into the ground. The wedge melts faster. The depression widens. The edges slump. Eventually, the surface collapses, creating a steep-sided hollow known in Russian as an alas.

In Siberia, these alases can be hundreds of meters across and tens of meters deep. They are filling with water, forming new lakes. And at the bottom of these lakes, the ancient organic soil is warming rapidly. Microbes that have been frozen since the Pleistocene are waking up, and they are hungry.

A study published in 2020 found that methane emissions from these thermokarst lakes are five times higher than previously estimated. The researchers drilled through the ice in winter, when the lakes were frozen over, and found bubbles trapped beneath the surface. When they pierced the ice with a hot needle, the gas ignited. It burned with a clear blue flame—methane, seeping out of the thawing earth, rising through the water column, accumulating beneath the ice, waiting for release.

This is the feedback loop in action. Warming thaws ice. Thaw creates lakes. Lakes warm the soil. Soil releases methane. Methane warms the planet. More ice thaws. More lakes form. More methane escapes.

We are not standing at the edge of this loop. We are already inside it. The question is not whether the permafrost will thaw. The question is how fast, how far, and whether we can slow it down.

The Yedoma Belt

There is a particular type of permafrost that keeps scientists awake at night. It is called Yedoma, and it is unlike any other frozen ground on Earth.

Yedoma formed during the Pleistocene, when the Mammoth Steppe was at its peak. Dust blowing off the glaciers settled on the landscape, accumulating millimeter by millimeter, century by century. This dust was rich in nutrients—calcium, potassium, phosphorus—and it fertilized the grasses that fed the herds. The grasses grew tall, died, and were buried by more dust. Their roots penetrated deep into the soil, pumping carbon underground. And then the cold came and froze it all.

Yedoma is characterized by its high ice content—often 50 to 90 percent by volume—and its extraordinary carbon density. A single hectare of Yedoma contains as much carbon as a hectare of Amazonian rainforest. But unlike rainforest carbon, which cycles rapidly through living biomass, Yedoma carbon has been locked away for tens of millennia. It is pristine. It is concentrated. And it is extremely vulnerable to thaw.

The Yedoma belt stretches across northeastern Siberia, through Alaska, and into the Yukon Territory. It covers approximately one million square kilometers—an area larger than Texas and California combined. It contains an estimated 400 billion tons of carbon, roughly one-quarter of the total permafrost carbon pool. And it is thawing faster than anyone predicted.

When Yedoma thaws, it does not simply soften. It collapses. The ice melts, the ground subsides, and the landscape is transformed from a flat plain into a chaotic jumble of hills and hollows. This is the thermokarst terrain at its most extreme. Scientists call it “badland” topography, and it is spreading.

The Abrupt Thaw

For many years, climate models assumed that permafrost thaw would be a gradual process. The ground would warm slowly, the active layer would deepen incrementally, and carbon would be released steadily over centuries. This assumption made the permafrost problem seem manageable. It was a chronic condition, not an acute emergency.

Then the scientists started looking at what was actually happening on the ground.

Abrupt thaw is the term they coined to describe the rapid, localized collapse of permafrost terrain. Unlike gradual thaw, which proceeds millimeter by millimeter from the surface downward, abrupt thaw occurs when ice-rich permafrost destabilizes and the ground literally falls apart. It happens in years, not decades. It can transform a stable landscape into a thermokarst swamp within a single human lifetime.

The implications for carbon emissions are staggering. Gradual thaw exposes a thin layer of soil to decomposition each year; the carbon escapes slowly, giving plants time to respond and potentially offset some of the losses. Abrupt thaw exposes the entire depth of the permafrost column at once. The carbon is released in a pulse, overwhelming any possible biological uptake.

Recent modeling studies suggest that abrupt thaw could double or triple the carbon emissions from permafrost by 2100. The models that policymakers have been relying on—the ones that inform the IPCC reports and the Paris Agreement targets—do not yet include these effects. They are underestimating the threat, possibly by a wide margin.

This is why rewilding is not just a nice idea. It is not just about preserving biodiversity or restoring wilderness. It is about preventing the abrupt thaw of millions of square kilometers of frozen ground. It is about buying time—time to decarbonize the economy, time to develop new technologies, time to adapt to the changes that are already inevitable. And the clock is ticking.

Part Two: The Memory of the Grass

The Lost Ecosystem

If you had stood on the land bridge between Siberia and Alaska twenty thousand years ago, you would not have recognized the place. There were no mosquitoes. There were no bogs. There was no spongy tundra sinking under your weight. There was no peat, no permafrost slumps, no drunken forests. Instead, you would have seen grass—acres and acres of grass, rippling in the wind like a golden ocean, stretching to the horizon and beyond.

This was the Mammoth Steppe. It was the largest terrestrial ecosystem on Earth, spanning from Spain in the west to Canada in the east, from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the steppes of Central Asia in the south. It covered much of what is now northern Europe, Siberia, and Alaska. It was cold and dry. Snowfall was light—perhaps 10 centimeters per year, compared to 50 centimeters or more in today’s Arctic. The winds swept unimpeded across the flat plains, scouring the snow from ridgetops and depositing it in valleys.

And it was teeming with life.

Herds of woolly mammoths migrated across this landscape, their tusks sweeping snow aside to reach the grass beneath. A single mammoth consumed 200 kilograms of vegetation per day. To support a population of one million mammoths—a conservative estimate for the peak of the Pleistocene—the steppe had to produce 200 million kilograms of grass daily. That is 73 billion kilograms per year, the equivalent of 10 million hay bales.

But the mammoths were only part of the story. Steppe bison, larger and longer-horned than their modern descendants, grazed alongside them. Wild horses galloped in bands of twenty or thirty, their hooves churning the soil. Reindeer moved in columns so vast that early explorers reported herds taking three days to pass a single point. Musk oxen huddled against the wind, their dense underwool protecting them from temperatures that dropped to -60°C. Saiga antelope, with their distinctive bulbous noses, filtered dust from the dry summer air. Cave lions, larger than modern African lions, stalked the edges of the herds. Wolves hunted in packs. Wolverines scavenged the kills. And everywhere, under everything, was the grass.

This was not a random collection of species. It was a machine. An ecological engine that had been running for millions of years, fine-tuned by evolution and competition. Every species had a role. Every interaction had a consequence.

The grass fed the grazers. The grazers fertilized the grass with their dung, returning nutrients to the soil in a form that plants could use immediately. Their hooves churned the soil, burying seeds and breaking up the moss that threatened to encroach. Their weight crushed saplings, preventing the spread of forest. Their migrations trampled the snow, compacting it so thin that the bitter cold of winter could penetrate deep into the earth.

And deep in that cold earth, the carbon stayed locked away.

Then the world changed.

The Great Dying

About fifteen thousand years ago, the climate began to warm. The glaciers that had covered much of North America and Europe for a hundred thousand years started to retreat. Sea levels rose, flooding the land bridge between Siberia and Alaska. The continental interior became warmer and wetter. The grasses that thrived in cold, dry conditions began to retreat northward.

But the climate alone did not kill the Mammoth Steppe. The steppe had survived previous interglacial warm periods. It had retreated and advanced, contracted and expanded, but it had always persisted. Something was different this time.

That something was us.

The evidence is circumstantial but compelling. The megafauna extinctions of the late Pleistocene were not simultaneous worldwide; they were staggered, occurring at different times on different continents. In Africa and southern Eurasia, where humans and large animals had coevolved for hundreds of millennia, extinction rates were relatively low. In the Americas and Australia, where humans arrived as a novel predator with advanced hunting technology, extinction rates approached 80 percent. In the Arctic, the pattern was intermediate—but the outcome was the same.

The mammoths went first. Then the horses, which vanished from North America and did not return until the Spanish brought them in the sixteenth century. Then the steppe bison, which survived in small pockets but never regained their former abundance. The cave lions, unable to find sufficient prey, starved. The woolly rhinoceros, that armored tank of the Ice Age, was no more.

And with the grazers gone, the grass died.

It happened slowly at first, then all at once. Without hooves to churn it, moss crept in. Moss is a poor substitute for grass. It is spongy and waterlogged; it insulates the ground rather than allowing cold to penetrate. It does not support deep root systems; its carbon is stored near the surface, vulnerable to decomposition. It is palatable to few herbivores; once established, it tends to stay.

Without teeth to crop them, shrubs took root. Willow, alder, and dwarf birch, previously kept in check by constant browsing, began to spread. Their dark branches absorbed sunlight that had once been reflected by snow. Their leaves, falling each autumn, added a layer of organic matter to the soil surface. Their roots, shallow and spreading, did nothing to stabilize the permafrost.

Without weight to crush them, saplings grew into trees. Larch and spruce advanced northward, colonizing ground that had been treeless for millennia. Forests are dark; they absorb heat. Forests are rough; they trap snow, increasing its insulating depth. Forests are inefficient carbon sinks above ground but even less efficient below ground, where their shallow roots barely scratch the surface of the soil.

The golden sea of grass fragmented, shrank, and finally drowned beneath a rising tide of peat, willow, and spruce. The Mammoth Steppe collapsed. In its place arose the ecosystem we now think of as “natural” Arctic: the boggy, mossy, shrub-choked tundra we see today.

It is not natural. It is the abandoned garden of a vanished civilization of animals. It is what happens when the gardeners leave and the weeds take over.

The Hypothesis

Sergey Zimov was not the first person to notice this. Paleontologists had been digging mammoth bones out of Siberian riverbanks for centuries. Explorers had marveled at the abundance of fossil remains. Indigenous peoples had incorporated mammoth ivory into their tools and art. But Zimov was the first to connect the dots in a new way.

In the 1980s, Zimov was a young geophysicist working at the Northeast Science Station in Chersky, a remote outpost on the Kolyma River in northeastern Siberia. He was studying permafrost, drilling cores and analyzing soil samples, trying to understand how this frozen landscape had formed and how it might respond to a warming climate. But he kept coming back to the bones. They were everywhere. The frozen earth was practically paved with them.

Standard scientific wisdom at the time held that the Mammoth Steppe disappeared because the climate became too warm and wet. The grass couldn’t survive, the argument went, so the animals starved. It was a simple, intuitive explanation, and it fit neatly with the prevailing view that climate is the primary driver of ecosystem change.

Zimov read this explanation and found it unsatisfying. Grass is resilient stuff. It grows in swamps and in deserts, on mountainsides and in river valleys. It tolerates heat and cold, drought and flood, fire and grazing. Why would a little warmth kill it? Why would a bit of rain cause its extinction?

What if, Zimov wondered, the causality ran the other way? What if the animals disappeared first—and the ecosystem collapsed because of their absence?

It was a radical idea. It challenged the assumption that vegetation determines herbivore populations and suggested instead that herbivores determine vegetation. It elevated animals from passive consumers to active engineers of their environment. It implied that the Arctic tundra was not the climax community, the final stage of ecological succession, but a degraded state. A shadow of what once was. A wound that had never healed.

And if animals created the steppe, then animals could bring it back.

The Counterargument

The scientific community did not embrace Zimov’s hypothesis with enthusiasm. Critics raised legitimate objections.

First, they said, the climate really was different. The Pleistocene was colder and drier than the Holocene. Even if we restored the herbivores, the grasses that dominated the Mammoth Steppe might not survive in today’s warmer, wetter conditions.

Second, they said, the herbivores themselves are different. The mammoth is extinct. The steppe bison is extinct. The horses that survived in domestication are not the same as their wild ancestors. The reindeer are still here, but their populations are a fraction of what they once were. We cannot recreate the past with stand-ins and proxies.

Third, they said, the scale is impossible. The Mammoth Steppe covered millions of square kilometers. We cannot fence that much land. We cannot manage that many animals. The idea is a fantasy, a distraction from real solutions.

Zimov heard these objections. He considered them carefully. He did not dismiss them out of hand. But he also recognized that they were arguments for inaction, and inaction had consequences of its own.

“You cannot prove that this will work,” he said, in an interview many years later. “But you also cannot prove that doing nothing will work. And we already know what doing nothing looks like. We are doing it now. The permafrost is thawing. The carbon is escaping. Doing nothing is not neutral. Doing nothing is a choice with consequences.”

So he built a fence.

Part Three: Pleistocene Park

The Beginning of an Experiment

In 1988, Sergey Zimov took his idea to the Soviet Academy of Sciences. He wanted to build a fenced enclosure in the middle of the Siberian tundra, stock it with large herbivores, and see what happened. The academy was skeptical. This was not how science was supposed to be done. You didn’t just stick animals in a field and wait. You had hypotheses. You had controls. You had grant applications, peer review, publication in prestigious journals.

Zimov had none of these things. He had a fence and a stubborn streak.

He started small. A few hectares. A handful of Yakutian horses—stocky, thick-necked animals bred by the Sakha people for millennia, perfectly adapted to the brutal Siberian winter. They were not wild horses; they were domesticated, descended from animals captured and tamed generations ago. But they were the closest living relative of the extinct Lena horse that once roamed these plains, and they retained many of their ancestors’ adaptations: dense winter coats, sturdy legs, hard hooves, and an instinctive drive to dig through snow for grass.

The first winter was brutal. The horses didn’t know how to find grass under the snow. They didn’t know how to break the ice crust with their hooves. They starved. They froze. Predators—wolves, primarily—picked off the weak ones. By spring, half the herd was dead.

Sergey’s son, Nikita, was a child then. He remembers watching his father lose animal after animal, year after year, without giving up. They tried different breeds. They tried different feeding strategies. They left hay in strategic locations to teach the horses where to dig. They selected for the most cold-hardy individuals, the ones that survived and thrived while others perished. Slowly, painfully, they learned.

By 1996, they were ready to expand. Pleistocene Park was officially established on 160 hectares of land near the Kolyma River. The fence went up. The animals arrived. And the experiment began in earnest.

The Zimov Method

Today, Nikita Zimov runs Pleistocene Park. Sergey, now in his late seventies, still works alongside him, but the daily burden falls on his son. Nikita lives in Chersky with his wife and young daughter. He spends his winters feeding thousands of animals by hand, hauling bales of hay across frozen rivers, repairing fences in -50°C temperatures, and defending his herd from wolves.

It is not glamorous work. There are no TED Talks in the Kolyma winter. No film crews, no journalists, no award ceremonies. There is only survival—his and the animals’.

But the results speak for themselves.

Pleistocene Park now covers 2,000 hectares—20 square kilometers—of restored grassland. The animal population includes Yakutian horses, reindeer, moose, musk oxen, European bison, and a small herd of Kalmykian cattle (a hardy breed that serves as a stand-in for extinct steppe bison). The park is not yet self-sustaining; Nikita must supplement the animals’ winter diet with hay. But the ecosystem is shifting.

Where there was moss, there is grass. Where there was shrub, there is open ground. Where the animals trample the snow, the soil temperature in February drops to -30°C—twenty degrees colder than the untrampled tundra just outside the fence. The permafrost beneath the park is stable. The carbon stays locked in the ground.

Critics sometimes point out that Pleistocene Park is too small to prove anything. Twenty square kilometers is a drop in the Arctic bucket, a rounding error in a landscape measured in millions of square kilometers. Nikita acknowledges this. He is not trying to save the planet with his 2,000 hectares. He is trying to demonstrate that the mechanism works. He is building a proof of concept, a living laboratory where scientists can measure the effects of grazing on permafrost with precision and rigor.

The question is whether anyone is willing to scale it up.

The Daily Work

A typical winter morning at Pleistocene Park begins long before sunrise. Nikita fires up the aging tractor—a Soviet-era MTZ-80, kept alive for decades by ingenuity and spare parts scavenged from abandoned equipment—and heads out to the hay barn. The bales weigh five hundred kilograms each. He loads one onto the tractor’s front fork, drives slowly to the horse enclosure, and breaks it apart with a pitchfork.

The horses come running. They know the sound of the tractor. They crowd around, shoving each other aside, their thick winter coats crusted with frost. Breath plumes from their nostrils in rhythmic jets. Their hooves crunch the snow into a hard-packed surface that will stay cold for months. Their eyes are calm; they trust him.

After the horses come the reindeer. Then the bison. Then the musk oxen, which refuse to approach the tractor and must be fed at a distance. Nikita makes three or four trips before lunch. By noon, the temperature has climbed to -35°C. By Arctic standards, this is a warm day.

In the afternoon, he checks the fence line. Permafrost heave shifts the wooden posts; wolves test the wire; the river ice, which serves as a natural barrier on one side of the park, cracks and reforms in unpredictable patterns. There is always something to fix. A broken insulator. A sagging wire. A post that has tilted forty-five degrees and needs to be reset.

In the evening, he compiles data. Soil thermometers buried throughout the park transmit readings to a central logger; Nikita downloads the files and checks for anomalies. Snow depth measurements are recorded by hand, entered into a spreadsheet. Camera traps capture images of the animals and the occasional predator. The data is meticulous, relentless, and essential.

This is what rewilding looks like on the ground. It is not a helicopter release of charismatic megafauna to the sound of orchestral music. It is frozen fingers and diesel fumes and hay dust in your lungs. It is incremental and unglamorous and utterly dependent on the stubbornness of a few dedicated people.

The Visitors

Despite its remoteness, Pleistocene Park receives a steady stream of visitors. Scientists come to study the animals and the soil. Journalists come to write stories about the mammoth project. Documentarians come to film the landscape and the light. Students come to learn and to help.

Nikita welcomes them all. He is not a charismatic evangelist; his manner is quiet, almost reserved. But he believes that the park’s story needs to be told, and he is willing to tell it as many times as necessary.

The visitors often arrive with romantic notions of rewilding. They imagine a pristine wilderness, untouched by human hands, where nature takes its course. Nikita disabuses them of this notion gently but firmly.

“Look at this fence,” he says, gesturing at the miles of wire that enclose the park. “This is not wilderness. This is a managed landscape. We feed the animals hay in winter because there is not enough grass yet to support them. We cull the males to maintain a balanced herd. We repair the fence when wolves break through. This is not nature untouched. This is nature restored, and restoration is work.”

The visitors nod. They take notes. They photograph the horses and the bison and the endless sky. They leave, changed by what they have seen, carrying the story of Pleistocene Park to the wider world.

Part Four: The Physics of Hooves

Snow as Blanket

To understand why the horses are so important, you have to understand snow.

Snow is an excellent insulator. Fresh, fluffy snow is about 90 percent air. The air pockets trap heat, preventing it from escaping the ground. If you have ever built a quinzhee—a snow shelter, hollowed out from a pile of powder—you know that the inside stays surprisingly warm even when the outside air is frigid. The snow holds your body heat in, reflecting it back at you from the walls.

The same principle applies to permafrost. In a typical Arctic winter, snow accumulates on the tundra and stays there. It does not melt until spring, and sometimes not until early summer. For six months or more, that snow blanket keeps the ground significantly warmer than the air above. At -40°C air temperature, the soil beneath a meter of snow might be -10°C or even -5°C. The snow is acting as a thermal buffer, smoothing out the extremes of winter cold.

That is too warm. At -5°C, permafrost is not actively thawing, but it is not actively freezing either. It is in a state of suspended animation, neither gaining nor losing ground. It is vulnerable to further warming. A few degrees of air temperature increase, a little more snow accumulation, a slightly longer autumn before the freeze sets in—and that -5°C becomes -2°C, then 0°C, then liquid.

Now introduce the horses.

A herd of horses moving across the landscape does not walk carefully. They trot, they run, they paw at the ground. They stop to sniff the air and then surge forward again. Their hooves punch through the snow crust and compress the powder beneath. They do not do this deliberately to save permafrost; they do it because they are hungry and the grass is underneath.

The effect is dramatic. Where horses have trampled, the snow density increases from about 0.1 grams per cubic centimeter to nearly 0.4 grams per cubic centimeter. The air pockets collapse. The insulating value plummets. Cold air from above can now penetrate deep into the soil, chilling it to temperatures that approach the atmospheric minimum.

In Pleistocene Park, the difference is stark. On untrampled tundra, the soil temperature at 50 centimeters depth hovers around -7°C throughout winter. On trampled grassland, the same depth reaches -25°C. That eighteen-degree difference is the difference between stable permafrost and vulnerable permafrost. That is the hoof effect.

The Mathematics of Compaction

The physics of snow compaction is well understood. Snow is a porous medium, a matrix of ice crystals separated by air-filled voids. When pressure is applied, the crystals fracture and rearrange, filling the voids and increasing density.

The relationship between density and thermal conductivity is exponential. A doubling of density produces approximately a fourfold increase in conductivity. The heat flows faster through the compacted snow, escaping to the atmosphere rather than remaining trapped in the ground.

Researchers at Pleistocene Park have developed a simple model to predict the effect of herbivore trampling on soil temperature. Input variables include snow depth, snow density, air temperature, and duration of cold period. The model outputs the minimum soil temperature reached during winter and the number of degree-days of cooling.

The results confirm what the Zimovs observed intuitively: herbivores are effective thermal engineers. A density of 0.4 grams per cubic centimeter—achievable with moderate trampling—is sufficient to allow soil temperatures to track air temperatures closely. A density of 0.5 grams per cubic centimeter—achievable with intensive trampling—essentially eliminates the insulating effect of snow altogether.

The challenge is achieving these densities at scale. Horses are effective tramplers, but they are also selective. They prefer certain areas—windblown ridges, south-facing slopes, places where snow is naturally thinner. They avoid others—dense shrub thickets, steep slopes, areas with deep, soft snow. A mixed-species herd, combining horses with lighter reindeer and heavier bison, can achieve more uniform coverage.

The Albedo Shift

Albedo is a measurement of reflectivity. It comes from the Latin word albus, meaning white. A surface with high albedo reflects most incoming solar radiation back into space. A surface with low albedo absorbs sunlight and converts it to heat.

Fresh snow has the highest albedo of any natural surface on Earth. It reflects about 85 percent of incoming solar radiation. This is why skiing on a sunny day feels warm even when the air temperature is below freezing—the snow is throwing the sun’s energy right back at you, warming your body from multiple directions.

Dark surfaces have low albedo. A black asphalt road reflects maybe 10 percent of sunlight and absorbs the rest. That absorbed energy turns into heat, which is why asphalt can burn your bare feet in summer. Open water has even lower albedo, reflecting only 5 to 10 percent of incoming radiation. This is why open water accelerates ice melt: it captures the sun’s energy and holds it.

In the Arctic, the albedo contrast between grassland and shrubland is stark. When snow covers grassland, the surface is uniformly white. The grass lies flat beneath the snow, invisible from above. Reflectivity is maximal. Solar energy is rejected.

When snow covers shrubland, the shrubs stick up through the snowpack. Their dark branches and twigs absorb sunlight and transfer heat to the surrounding snow, accelerating melt. A patchy snowpack reflects less light and absorbs more energy. The local area warms. The melt accelerates. Bare ground appears earlier in spring, absorbing even more energy and warming the soil further.

The animals of Pleistocene Park accelerate the shift from shrubland to grassland. They browse on willow and alder, eating the branches that would otherwise protrude through the snow. They trample seedlings, preventing shrubs from establishing. They fertilize the grass, helping it outcompete its woody rivals. They create the conditions for high albedo and maintain them through grazing pressure.

Every hoof that crushes a willow sapling is a small act of climate engineering. Multiplied by thousands of animals across millions of hectares, it becomes a planetary force.

The Root System

Grasslands and forests store carbon differently. A tree stores most of its carbon above ground, in its trunk and branches. The trunk is structural, built to resist wind and support the weight of the canopy. It is dense and slow-growing, accumulating carbon over decades or centuries. When the tree dies and rots, that carbon is released back to the atmosphere relatively quickly. A forest fire releases it instantly, in a pulse of smoke and ash.

A grassland stores most of its carbon below ground, in the roots. Grass plants die back to the soil surface each winter, but their roots persist, growing deeper year after year. Some prairie grasses have root systems that extend three meters into the earth—deeper than the trunks of many trees are tall. When those roots die, they become soil organic matter, locked away from the atmosphere, protected from fire and rapid decomposition.

This is why grassland soils are so deep and dark. The black earth of the Ukrainian steppe, the chernozem of the American plains, the mollisols of the Argentine pampas—these are not products of surface growth. They are products of root death. Century after century, roots grow, roots die, roots become soil. The carbon migrates downward, away from the surface, away from disturbance, away from rapid cycling.

In the Arctic, this process has been reversed. Mosses and sedges, the dominant plants of the wet tundra, have shallow root systems. They store carbon near the surface, in the top few centimeters of soil, where it is vulnerable to thaw and decomposition. When the permafrost collapses, that shallow carbon goes first, flushed into lakes and rivers, consumed by microbes, exhaled as CO₂ and methane.

Restoring grassland means restoring deep roots. It means shifting the carbon storage zone from the top ten centimeters to the top hundred centimeters. It means taking carbon that is currently vulnerable to thaw and reburying it in the deep freezer. It means transforming the Arctic from a carbon source back into a carbon sink.

The Winter Graze

There is a persistent myth that Arctic herbivores migrate south for the winter to find food. Reindeer do migrate, but they do not necessarily go south. They go to windblown ridges where the snow is thin and the grass is accessible. They go to frozen lakes where they can scrape away the thin snow cover. They go to forest edges where the canopy intercepts snowfall and the ground beneath remains relatively bare. They follow the food.

In the Pleistocene, these migrations were massive. Tens of millions of animals moving in synchronized waves across the continent, trampling snow as they went. Their hooves prepared the grazing grounds for their own return. It was a self-sustaining cycle: migration compacted snow, compaction preserved grass, grass attracted migrants.

Today, domestic reindeer herders in Scandinavia and Russia still practice a version of this migration. They move their animals between summer pastures in the north and winter pastures in the forest edge, following routes established over generations. The snow is thinner in the forest. The lichen is abundant. The reindeer thrive.

But the herders are under pressure. Climate change brings rain-on-snow events that freeze the tundra into an impenetrable ice crust, trapping the lichen beneath a shell that hooves cannot break. Industrial development fragments the migration corridors, cutting traditional routes with roads, pipelines, and railways. Forestry operations replace lichen-rich old growth with dense, unproductive plantations that shade out the ground vegetation.

The herders know what they need: more animals, more movement, more trampling. They have known this for centuries. They have practiced adaptive grazing management since before the term existed. Now the climate scientists are catching up.

Part Five: The Grazers

The Horse: The Foundation Species

The Yakutian horse is a living relic. DNA analysis suggests the breed diverged from other horse lineages about 15,000 years ago—right around the time the Mammoth Steppe began to collapse. They are not descended from the horses that Russian settlers brought to Siberia in the seventeenth century; they were already there, surviving in isolated pockets, waiting.

These horses are built for cold. Their coats grow so thick in winter that they can sleep in the open at -60°C. The guard hairs are long and coarse, shedding snow and ice. The undercoat is dense and woolly, trapping a layer of warm air against the skin. Their legs are short and stocky, reducing surface area and heat loss. Their ears are small, their muzzles are furry, their tails are bushy. They look less like horses and more like oversized Shetland ponies on steroids.

But their most important adaptation is behavioral. Yakutian horses are compulsive diggers. Presented with a snow-covered field, they do not wander aimlessly; they immediately begin pawing. They uncover grass, they eat, they move on. They leave behind a network of feeding craters that expose bare ground and allow the cold to penetrate. A single horse can dig dozens of craters in a day, each one a tiny window of cold air reaching down to the permafrost.

Sergey Zimov calls horses the “tractors” of the steppe. They are the heavy equipment. Without them, restoration is impossible. With them, everything else follows.

The Reindeer: The Cold Air Pump

Recent research has elevated the reindeer to a starring role in the rewilding narrative. A 2023 study from the Research Institute for Sustainability modeled the climate impact of reindeer herding and found something surprising: reindeer don’t just preserve permafrost; they actively cool the soil.

The mechanism is subtle. Reindeer are lighter than horses and bison. They do not compact snow as thoroughly. But they graze lichen, which is pale in color and reflects sunlight. When reindeer remove lichen, they expose darker soil beneath, which absorbs more heat. This seems like it would be a problem—but the soil warming occurs in summer, when the sun is high, and the effect is offset by the winter cooling from trampling.

More importantly, reindeer are mobile. A single reindeer herd can travel hundreds of kilometers in a season, spreading the hoof effect across a vast area. Their migration routes are highways of cold air, stitching together patches of compacted snow into a continuous fabric. A reindeer hoof print may be small, but a million reindeer make a million hoof prints, and a million hoof prints change the landscape.

The study also noted an economic benefit. Reindeer meat has a carbon footprint approximately 90 percent lower than beef. It is produced on land that cannot support crops or conventional livestock. It supports Indigenous communities that have managed these herds for centuries. If the world shifted a portion of its meat consumption to reindeer—already a traditional food source for northern peoples—the emissions savings would be substantial. It is a rare example of a climate solution that also makes economic sense, supports cultural survival, and restores ecological function.

The Bison and Musk Ox: The Heavyweights

Horses can trample snow. Reindeer can migrate long distances. But neither can effectively control woody vegetation. Saplings that escape the horses’ hooves and the reindeer’s teeth will eventually become trees. Trees are the enemy of grasslands. They are dark, they trap snow, they sequester carbon above ground where it is vulnerable to fire. They must be controlled.

Enter the bison.

European bison, also known as wisent, are the heaviest land animals in Europe. A large bull can weigh nearly a ton. They are not agile; they do not need to be. When a bison encounters a sapling, it does not carefully browse the leaves. It simply leans on the tree until it breaks. Then it eats the broken branches at its leisure, stripping the bark and crushing the wood.

Bison also wallow. They roll in dust and mud to dislodge parasites and cool themselves, creating depressions in the soil that collect water and promote plant diversity. A bison wallow is a microhabitat, a tiny wetland that supports insects, amphibians, and birds. In a landscape dominated by grass, wallows provide essential variety. They are the punctuation marks in the long sentence of the steppe.

Musk oxen fill a similar niche in the high Arctic, where bison cannot survive. Their thick underwool, qiviut, is warmer than cashmere and eight times warmer than sheep’s wool. It sheds snow and insulates against the most extreme cold. They huddle together in defensive circles when wolves approach, their massive heads forming an impenetrable barrier, their sharp hooves ready to strike. They are the ultimate cold-weather specialists, the last survivors of a megafauna community that once included mammoths and woolly rhinos.

The Moose: The Pruner

Moose are often overlooked in rewilding discussions. They are not grazers; they are browsers, preferring willow and birch leaves to grass. In a pure grassland restoration, moose would have no place. They would be competitors rather than collaborators.

But the Arctic is not becoming pure grassland overnight. It is currently shrubland, thick with willow thickets that moose adore. Allowing moose to browse these shrubs is a form of biological control. The moose eat the leaves, reducing the shrubs’ ability to photosynthesize. They break branches as they feed, damaging the plants’ structure. They trample seedlings, preventing regeneration. They deposit dung, fertilizing the grass that competes with the shrubs.

A landscape with moose is a landscape where shrubs struggle to dominate. And a landscape where shrubs struggle is a landscape where grass can gain a foothold. The moose are not the final destination of rewilding; they are the transitional phase, the bridge between shrubland and grassland. They prepare the ground for the grazers that will follow.

The Mammoth: The Missing Link

There is one animal missing from Pleistocene Park. It is the animal that gives the park its name. It is the animal that, more than any other, defined the Mammoth Steppe ecosystem. It is the animal whose tusks still litter the Siberian riverbanks, whose bones have been used for centuries to make tools and art, whose image adorns cave walls from France to Russia.

The woolly mammoth.

Nikita Zimov does not pretend that bringing back mammoths will be easy. The technical challenges are immense. The ethical questions are unresolved. The public perception is fraught with Jurassic Park comparisons and fears of playing God. But he believes—cautiously, pragmatically, without hype or exaggeration—that it is possible.

The work is happening not in Siberia but at Harvard University, in the laboratory of geneticist George Church. Church’s team has sequenced the complete genome of the woolly mammoth from frozen carcasses recovered from the permafrost. They have compared it to the genome of the Asian elephant, the mammoth’s closest living relative. They have identified the genes responsible for mammoth-specific traits: the shaggy coat, the small ears, the dome-shaped head, the cold-tolerant hemoglobin, the fat deposits that provided insulation and energy reserves.

Using CRISPR gene-editing technology, they are inserting these mammoth genes into Asian elephant cells. They are not attempting to create a perfect mammoth clone—that would require intact DNA, which does not exist, and a surrogate mother, which raises immense ethical concerns. They are attempting to create a cold-adapted elephant, a hybrid that carries enough mammoth traits to survive in the Siberian winter and perform mammoth ecological functions.

The first calves could arrive within a decade. They will not be mammoths in the full sense. They will be approximations, living proxies, woolly elephants with mammoth genes. But they will be capable of doing mammoth work: knocking down trees, dispersing seeds, maintaining the grassland, trampling snow.

Critics argue that this is a distraction. Why pour millions of dollars into resurrecting an extinct species when living species are themselves going extinct at unprecedented rates? Why create mammoths when we cannot save elephants, rhinos, and tigers from poaching and habitat loss?

Nikita Zimov has heard these arguments. He does not dismiss them. He acknowledges the ethical complexity of de-extinction and the legitimate concerns of conservation biologists. But he notes that the mammoth is not just a species. It is a keystone, an ecosystem engineer, a shaper of landscapes. Restoring the mammoth is not about nostalgia or technological spectacle. It is about restoring function to a broken system.

“We don’t need mammoths because we miss them,” he says. “We need mammoths because they do something that no other animal does. They push over trees. They break the forest. They keep the grassland open. Without them, the shrubs and trees will keep advancing, and the permafrost will keep thawing. If we can create an animal that does that job, we should do it.”

The Smaller Players

The megafauna get all the attention, but the smaller animals matter too.

Arctic ground squirrels dig burrows that aerate the soil and create microsites for seed germination. Lemmings graze vegetation and fertilize the tundra with their droppings; their population cycles drive the dynamics of predators and prey across the entire ecosystem. Voles and shrews consume insects and spread fungal spores. Birds disperse seeds and deposit nutrients from distant foraging grounds.

A complete rewilding strategy must account for these smaller players. They are not substitutes for the megafauna, but they are essential components of a functioning ecosystem. The return of the large herbivores will create conditions that benefit the small herbivores, which in turn will support the predators and scavengers that complete the food web.

This is the beauty of rewilding: it is not about individual species but about ecological networks. Restore the keystone, and the rest follows.

Part Six: The Economics of Ice

The Price of a Horse

Let us talk about money. It is uncomfortable to put a price tag on a living creature, to reduce a breathing, feeling animal to a line item in a budget spreadsheet. But if we are serious about scaling rewilding to the continental level, we must do the math. We must account for costs and benefits, investments and returns. We must make the economic case as compelling as the ecological one.

A Yakutian horse costs about $500 to purchase in Siberia. Transporting it to a remote location—by truck, by barge, by helicopter if necessary—adds another $200. Feeding it through the winter costs about $150 in hay, delivered in bales that must be harvested, baled, transported, and stored. Veterinary care, fencing, and monitoring add perhaps $100 per year. Over a ten-year lifespan, a single horse represents an investment of roughly $2,500.

A bison is more expensive. European bison are rare and carefully managed; acquiring a breeding pair can cost $15,000. Musk oxen are harder still, requiring permits from multiple jurisdictions and specialized handling facilities. Reindeer are relatively cheap—a few hundred dollars per animal—but they require herders, and herders require salaries, housing, and equipment.

Now multiply by the number of animals needed to make a measurable climate impact.

The Oxford study mentioned earlier proposed a starting target of three large experimental areas, each containing approximately 1,000 animals. The total cost over ten years, including land acquisition, fencing, animal purchases, feeding, and personnel, came to $114 million USD.

That is a lot of money. It is also, in the context of global climate finance, a rounding error.

The Green Climate Fund, established by the United Nations to help developing countries reduce emissions and adapt to climate change, has committed over $10 billion since 2015. The Global Environment Facility distributes another $1 billion annually. The Inflation Reduction Act in the United States allocates nearly $400 billion for climate and energy programs over ten years. The Bezos Earth Fund has pledged $10 billion for climate initiatives.

We are not looking for money that does not exist. We are looking for a reallocation of money already committed. We are looking for a shift in priorities, a recognition that preserving permafrost is as urgent as deploying solar panels and as cost-effective as improving energy efficiency.

The Carbon Economy

The economic case for rewilding depends critically on the price of carbon. Carbon pricing is the mechanism by which we assign a monetary value to the damage caused by greenhouse gas emissions. It is not a perfect system; it is subject to political manipulation and market failures. But it is the best tool we have for comparing the costs of emission reductions across different sectors and strategies.

At a carbon price of $5 per ton, the 72,000 tonnes of carbon preserved annually by a thousand-animal herd is worth $360,000. This barely covers operating costs. At $50 per ton—the price recommended by the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices, co-chaired by Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz—the same carbon is worth $3.6 million. At $100 per ton, a price that many economists consider necessary to meet the Paris Agreement targets, it is worth $7.2 million.

The European Union’s Emissions Trading System, the world’s largest carbon market, has seen prices fluctuate between €50 and €100 per ton in recent years. If similar prices were applied to permafrost carbon, rewilding would not merely be viable. It would be profitable.

Of course, there is a catch. The carbon preserved by rewilding is not being emitted. It is staying in the ground, frozen and inert. This is fundamentally different from capturing carbon that has already been emitted, which can be measured directly at the stack or in the atmosphere. Measuring avoided emissions is harder than measuring captured emissions. Verifying that the permafrost would have thawed without the animals is a counterfactual claim, difficult to prove to the satisfaction of carbon accountants and regulators.

But the alternative—doing nothing and watching the permafrost thaw—is also difficult to verify. We cannot run a controlled experiment on the entire Arctic, with half the permafrost protected and half left to thaw. We have to act on the best available evidence, imperfect as it may be.

The Ancillary Economy

Rewilding does not produce only carbon credits. It produces meat, hides, antlers, and tourism revenue.

A single reindeer yields about 50 kilograms of meat. At current market prices in Scandinavia, that is roughly $500. A herd of 10,000 reindeer, sustainably harvested at a rate of 20 percent per year, can generate $5 million annually in meat sales alone. Bison meat commands premium prices in Europe and North America, often exceeding $10 per kilogram. Musk ox qiviut, harvested during the spring molt, sells for $80 per ounce—more than cashmere, more than alpaca, more than most luxury fibers.

Tourism is harder to quantify but potentially more valuable. Pleistocene Park currently receives a few hundred visitors per year, mostly scientists and journalists who arrange their own transportation and accommodation. If the park expanded and added infrastructure—cabins, guided tours, interpretive centers, research facilities—it could attract thousands. Ecotourists pay premium rates for authentic wildlife experiences. A landscape with bison, musk oxen, and the prospect of seeing a mammoth-elephant hybrid would be a global attraction, drawing visitors from every continent.

None of these revenues will make rewilding self-funding at the necessary scale. But they will offset costs and provide local employment. They transform rewilding from a charity case into an economic development strategy, from a drain on public resources into a source of private income.

The Cost of Inaction

There is another number that rarely appears in budget calculations. It is the number that represents the cost of doing nothing.

If the permafrost thaws completely, releasing its 1,600 billion tons of carbon, the resulting climate feedback will overwhelm all other mitigation efforts. The Paris Agreement targets will become unachievable. Sea levels will rise meters, not centimeters. Agricultural systems will destabilize as weather patterns shift and extreme events multiply. The global economy will contract. Hundreds of millions of people will be displaced.

Economists call this the social cost of carbon. The current U.S. government estimate is $51 per ton. Some researchers argue the true figure is closer to $200, once you account for factors that the official models omit: loss of biodiversity, cultural heritage, human health, political instability. At $200 per ton, the permafrost carbon represents $320 trillion in potential damages—roughly four times the annual global GDP.

This is not a precise calculation. It is a thought experiment, an attempt to grasp the scale of what is at stake. But it clarifies the fundamental choice.

We can spend billions now to keep the carbon frozen. Or we can spend trillions later to adapt to a world that has already thawed.

The Investment Gap

The gap between current investment in permafrost preservation and the level needed for meaningful climate impact is vast. Total annual spending on permafrost research, monitoring, and intervention is probably less than $100 million globally—a fraction of what we spend on fusion energy, carbon capture, or geoengineering.

This is not because permafrost is unimportant. It is because permafrost is remote, invisible, and poorly understood. It lacks the political constituency of renewable energy or the technological glamour of electric vehicles. It is not a problem that can be solved by a single breakthrough invention or a single policy change.

Closing the investment gap will require a sustained, coordinated effort from governments, foundations, and private investors. It will require treating permafrost preservation as a public good, like national defense or clean air, that cannot be left to market forces alone. It will require recognizing that the benefits of intervention—a stable climate, intact coastlines, preserved communities—are widely distributed, while the costs are concentrated among a few.

This is not impossible. We have done it before. We have built highways and airports and telecommunications networks. We have funded basic science and medical research. We have created social insurance programs and environmental regulations. We know how to mobilize capital for public purposes when we choose to do so.

The question is whether we will choose to do so for the permafrost.

Part Seven: The Human Landscape

The People of the Cold

The Arctic is not a wilderness. It has never been a wilderness. It has been inhabited for at least 30,000 years, since the first humans crossed the land bridge from Asia to America, pursuing mammoths and bison across the grassy plains. It is home to approximately four million people today, including dozens of Indigenous nations with distinct languages, cultures, and economies.

For these communities, rewilding is not a theoretical exercise. It is not an abstract proposal to be debated at academic conferences or modeled in computer simulations. It is a proposal to fundamentally reshape the landscape they depend on for food, transportation, and cultural identity. Their voices must be central to the conversation.

Consider the Nenets of northwestern Siberia. For centuries, the Nenets have migrated across the Yamal Peninsula with their reindeer herds, following the seasons and the grazing. Their entire culture is organized around the herd. Their diet—reindeer meat, reindeer blood, reindeer marrow—derives from it. Their clothing—reindeer skin boots, reindeer fur coats, reindeer sinew thread—derives from it. Their shelter—the conical chum, covered with reindeer hides in winter and birch bark in summer—derives from it. Their social structure, their spiritual beliefs, their oral traditions—all derive from reindeer.

Climate change threatens the Nenets way of life. Rain-on-snow events, increasingly common in a warming Arctic, freeze the tundra into an impenetrable ice crust. The reindeer cannot dig through to reach the lichen beneath. They starve by the thousands. In 2013, a single rain-on-snow event killed 60,000 reindeer on the Yamal Peninsula—roughly 20 percent of the total herd. The herders watched their animals die and could do nothing to save them.

Rewilding could help. More reindeer, more trampling, more compaction of snow—these are not foreign concepts to the Nenets. They have been managing grazing pressure for generations. They know which pastures recover quickly and which require rest. They know how snow density varies with wind exposure and topography. They know the migration routes that their ancestors followed and the signs that indicate when to move.

But they also know that outsiders rarely listen. Scientists arrive with their instruments and their hypotheses, collect data, publish papers, and leave. Journalists arrive with their cameras and their questions, capture images, write stories, and move on. The Nenets remain, dealing with the consequences.

The Sámi and the Forests

In northern Scandinavia, the Sámi reindeer herders face a different challenge. Their grazing lands are increasingly fragmented by forestry operations. Clear-cuts remove the old-growth forests where ground lichen—the reindeer’s winter food—grows most abundantly. Plantations of fast-growing pine create dense canopies that shade out understory vegetation. The herders are forced to feed their animals expensive supplemental fodder or reduce herd sizes, sacrificing the productivity that has sustained their communities for generations.

The irony is that forestry is a major driver of permafrost thaw in Scandinavia. Clear-cutting removes the insulating snow-holding capacity of the forest canopy, but it also removes the trees’ ability to shade the ground in summer. The soil warms. The permafrost degrades. Carbon is released.

Torben Windirsch, a researcher specializing in permafrost-grazing interactions, has proposed a simple solution: bring the reindeer back to the cut blocks. Allow the herders to graze their animals on recently harvested forest land. The reindeer will trample the snow, cooling the soil. They will fertilize the ground with their dung. They will browse on regenerating saplings, reducing competition with planted trees. They will restore the lichen communities that take decades to recover naturally.

It is a textbook win-win. The forestry companies get healthier soils and potentially faster timber growth. The herders get access to traditional grazing grounds. The climate gets permafrost preservation. The reindeer get food.

Yet implementation remains elusive. The regulatory framework governing forestry in Sweden and Finland does not recognize reindeer grazing as a legitimate land use on cut blocks. The herders are consulted but not empowered. Their knowledge is solicited but not integrated. The companies cite logistical challenges and market pressures; the governments cite existing policies and competing priorities.

Windirsch continues to advocate for policy change. He organizes workshops, publishes papers, briefs officials. He is patient but persistent. “The herders have been doing this for a thousand years,” he says. “We should be learning from them, not telling them how to do their jobs.”

The Sakha and the Horses

In the Sakha Republic of northeastern Siberia, the horse is not just an animal. It is a cultural icon, a symbol of resilience and adaptation, a companion in survival. The Sakha people have bred Yakutian horses for centuries, developing a strain uniquely suited to the extreme cold. A Sakha family’s wealth was traditionally measured in horses.

Soviet collectivization devastated Sakha horse culture. Private herds were confiscated. Traditional breeding knowledge was suppressed. The horses themselves were crossbred with larger Russian draft breeds, diluting the cold-hardy genetics that had been refined over generations. By the 1980s, pure Yakutian horses were rare, confined to a few remote villages where collectivization had been incomplete.

Today, there is a revival underway. Sakha horse breeders are working to restore the pure Yakutian strain, using DNA testing and careful breeding selections. The demand for Yakutian horses is rising, driven in part by the rewilding movement. Pleistocene Park buys its horses from Sakha breeders, paying premium prices for quality animals. Other rewilding projects in Russia and beyond are following suit.

This is rewilding as it should be: not a top-down intervention imposed by outsiders, but a collaboration between scientific researchers and Indigenous knowledge holders. The Zimovs do not pretend to know more about horses than the Sakha. They defer to local expertise, adapt their methods to local conditions, and share credit for their successes.

“The horses are Sakha horses,” Nikita Zimov says. “The herders are Sakha herders. The land is Sakha land. We are just guests here, trying to help.”

The Ethics of Intervention

Rewilding raises difficult ethical questions. Is it right to introduce large herbivores to landscapes that have not supported them for millennia? What if they compete with native species for food or habitat? What if they alter ecosystems in unpredictable ways, triggering cascading effects that we cannot foresee? What if they become invasive, spreading beyond their intended range and causing damage to agriculture or infrastructure?

These questions deserve serious consideration. They cannot be dismissed with appeals to urgency or necessity. They must be addressed honestly, transparently, and humbly.

But the alternative—non-intervention—is also an intervention. By choosing to do nothing, we are choosing to allow the current trajectory to continue. That trajectory includes the extinction of species unable to adapt to rapid warming. It includes the collapse of ecosystems that have existed for thousands of years. It includes the displacement of human communities whose homelands are becoming uninhabitable. It includes the release of carbon that will accelerate climate change for centuries.

Non-intervention is not neutrality. It is a decision with consequences as profound as any active intervention. The question is not whether we will intervene. We are already intervening, every day, by burning fossil fuels and emitting greenhouse gases. The question is whether we will intervene intelligently, deliberately, and ethically.

The Consultation Imperative

Any large-scale rewilding effort must begin with consultation. Not after the plans are made, not when the funding is secured, not when the animals are already on the trucks—but at the very beginning, when the idea is still taking shape.

Consultation means more than informing communities about decisions that have already been made. It means listening. It means incorporating local knowledge into project design. It means respecting Indigenous sovereignty and territorial rights. It means sharing benefits equitably and acknowledging the historical injustices that have shaped current land tenure patterns.

This is not just an ethical imperative. It is a practical one. Rewilding projects that ignore local communities fail. They fail because fences are cut, animals are poached, and political opposition derails implementation. They fail because they are perceived as impositions rather than partnerships.

Rewilding projects that engage local communities succeed. They succeed because herders contribute their knowledge of animal behavior and pasture dynamics. They succeed because hunters assist with predator management and population monitoring. They succeed because local people have a stake in the outcome and take ownership of the process.

The Zimovs learned this lesson through experience. In the early years of Pleistocene Park, they faced skepticism and resistance from neighboring communities. Why should they care about permafrost and carbon and climate change? These were distant concerns, abstract and irrelevant to daily life.

Over time, the Zimovs shifted their approach. They hired local workers. They bought supplies from local businesses. They invited school groups to visit the park and see the animals. They explained their work in terms that resonated: healthy pastures, abundant game, stable ground, economic opportunity.

The skepticism did not disappear overnight. But it softened. Today, Pleistocene Park is a source of pride for Chersky. It is recognized as a valuable asset, not a foreign imposition.

Part Eight: The Obstacles

The Scale Barrier

The most frequently cited objection to Pleistocene rewilding is the scale problem. Pleistocene Park is 20 square kilometers. The Arctic permafrost zone is approximately 18 million square kilometers. To have a measurable impact on global climate, we would need to replicate the Pleistocene Park experiment across an area the size of Mexico.

This is, on the face of it, absurd. We cannot fence off millions of square kilometers. We cannot airlift millions of bison and horses to Siberia. We cannot feed them hay through the winter. The logistics alone are prohibitive. The costs are astronomical. The political barriers are insurmountable.

But this objection misunderstands the nature of the proposal. No one is suggesting that we build a fence around the entire Arctic. No one is suggesting that we micromanage every hectare of tundra. The proposal is to restore the ecological processes that maintained the Mammoth Steppe, and then allow those processes to propagate naturally.

Horses reproduce. Bison reproduce. Reindeer reproduce. A founder population of a few thousand animals, given sufficient habitat and protection, can grow to hundreds of thousands within decades. Their range will expand outward from the initial release sites as populations increase and competition for resources intensifies.

The fence at Pleistocene Park is not a permanent enclosure. It is a temporary measure to protect the founding herd from predators and poaching during the critical early years. Nikita Zimov already allows some animals to range outside the fence. As the population grows, he will open more territory. Eventually, the fence may become obsolete.

The goal is not to micromanage the Arctic ecosystem. The goal is to jump-start it and then step back. To provide the initial push that sets the system in motion. To restore the keystone species and let them do what they have always done.

The Reproduction Bottleneck

Even with optimal conditions, large herbivores reproduce slowly. Elephants gestate for 22 months and produce a single calf. Bison carry their young for 9 months and usually bear one calf per year. Horses are similar. Reindeer are faster—a healthy cow can produce a calf annually from age two—but they are also smaller, and their per-animal impact on snow compaction is lower.

Mathematical models suggest that it would take at least 50 years to reach self-sustaining population densities across significant portions of the Arctic. This is not an argument against rewilding; it is an argument for starting now. Every year we delay is a year of population growth lost. Every year we wait, the permafrost thaws a little more.

There are strategies to accelerate the process. Assisted reproduction technologies—artificial insemination, embryo transfer, in vitro fertilization—could increase reproductive rates in captive breeding programs. Genetic selection for twinning, though controversial and ethically complex, could double calf production. Supplementary feeding during winter could reduce mortality and improve body condition for breeding.

These are not immediate solutions. They require research, investment, and careful ethical consideration. But they are worth exploring.

The Infrastructure Gap

The Arctic lacks the infrastructure to support large-scale rewilding. There are few roads, fewer railways, and a limited network of airports. Fuel is expensive. Labor is scarce. Supply chains are fragile. A single winter storm can cut off a community for weeks.

This is not an accident. The Arctic is sparsely populated precisely because it is difficult to access and expensive to develop. Rewilding advocates must confront this reality. They cannot wish it away.

One potential solution is to piggyback on existing industrial infrastructure. Oil and gas companies maintain roads, airstrips, and port facilities in many parts of the Arctic. These were built for resource extraction, but they could serve rewilding operations as well. Partnerships between conservation organizations and energy companies are uncomfortable—the goals of the two sectors are often in direct conflict—but perhaps necessary.

Another approach is to prioritize rewilding in areas that already have some infrastructure. The Yamal Peninsula, with its gas fields and rail connections, is more accessible than the remote eastern Siberian coast. Northern Scandinavia has excellent roads and reliable supply chains. Alaska has a highway system reaching deep into the interior. Canada has winter roads that, though seasonal, provide a window for heavy equipment transport.

We do not need to rewild the entire Arctic simultaneously. We can start in accessible locations and expand outward as infrastructure improves and populations grow.

The Predator Problem

Wolves are a fact of life in the Arctic. They have always preyed on large herbivores, and they will continue to do so. A rewilded landscape must accommodate both predators and prey.

In Pleistocene Park, wolves occasionally breach the fence and kill horses. Nikita Zimov does not shoot them. He repairs the fence and accepts the losses. He considers wolf predation a natural part of the ecosystem he is trying to restore. The wolves are not invaders; they are returning natives, reclaiming their ancestral hunting grounds.